|

I do not like breaches in the sand, I do not like them Sam I am... Most years we focus our attention on fixing an entire beach profile from the berm to the water. We spend our energy and sand budget trying to rebuild a beach that's super for horseshoe crab spawning and, in turn, super for shorebird foraging. However, this year we are trying to address breaches (gaps) in several beach berms that create horseshoe crab traps during the spawning season. These low spots along the beach allow the high tide waters to flow into the marsh, taking with it thousands of horseshoe crabs. In previous years volunteer efforts were undertaken to save as many crabs as possible, but this task is huge and outpaces capacity. Thankfully, we received funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to address some of the more problematic breaches on Delaware Bay beaches in Middle Township, Cape May County, NJ. Beach breaches along the Delaware Bay are most often the result of historic land uses and land management decisions that have left the marshes backing the beach at unnaturally low elevations. These low marsh areas do not provide the "backbone" needed to support the beach berm, as a result the beaches fall back into the marsh and create a breach. Until we can fix all of the marshes along the Delaware Bay, our best effort to address the issue of beach breaches in the short-term is adding sand to the berm. By building up the low areas to match the adjacent berm elevations we hope to reduce the number of times the tide sends horseshoe crabs careening into the marsh. To provide further resiliency to the system we will be planting thousands of beach grass culms to anchor the berms. Wildlife Restoration Partnerships is overseeing the construction activities that began this week on S. Reeds Beach where 650 tons of sand were brought in to close up a breach that caused thousands of crabs to die in previous years. The project site was marked out for specific elevations by Stockton University's Coastal Research Center. Then sand is brought in by truck and moved down the beach to the project site with heavy machinery. The contractor finishes the berm restoration by profiling the sand to meet the target elevations.

Next week we will be fixing breaches at Pierces Point and Kimbles Beach with another 4,500 tons of sand. We appreciate all of the input and effort that went into getting this project underway from NJDEP's Division of Land Resource Protection, U.S. Army Corps, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

1 Comment

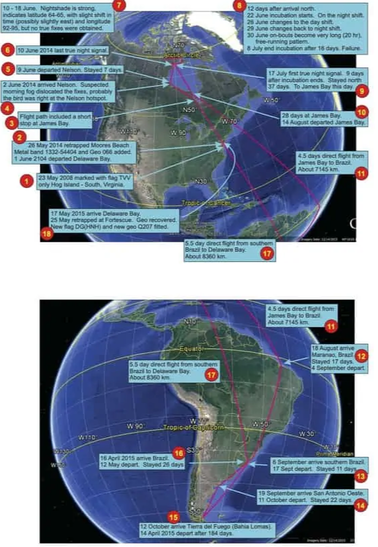

The following is a report from our partner Dr. Larry J. Niles of Wildlife Restoration Partnerships. It was initially posted on his website: A Rube With a View. Direct Flight to the Arctic or Stopover?A migratory stopover for arctic nesting shorebirds must provide each bird the energy necessary to get to the next stopover or to the ultimate destination, the wintering or breeding area. Delaware Bay stands out among these shorebird refueling stops because it delivers fuel in the form of horseshoe crab eggs giving birds options. Our telemetry has shown that Red knots, the species we best understand, may leave Delaware Bay and go directly to their Arctic breeding areas, or stopover on Hudson Bay. The choice of going straight to the breeding area or stop at another stopover may be critical to understanding the ecological dramas now underway on Delaware Bay. This year has been like none of the 23 years we have studied shorebirds and horseshoe crabs on Delaware Bay. As I described in these updates, persistent northeast winds caused two unusual conditions that affected red knots and the other shorebirds species, ruddy turnstones, semipalmated sandpipers, dunlin, short-billed dowitcher, and sanderlings. First, the wind blowing in from the cold ocean chilled the bay and slowed the horseshoe crab spawning to nearly a standstill until the last week of May. Whereas in other years, we would have seen tiny ribbons of eggs threading the tideline, this year we have none. Shorebirds depend on this natural largess, gobbling eggs with almost no effort and laying down weight like starving people at a fast-food restaurant. Instead, this year they must hunt them down by scouring the bay for any odd pockets of crab spawning. Not only is there not enough, but the search burns valuable energy reserves that should ultimately go to the flight to the Arctic and breeding. The second impact of the odd weather events of May came when Tropical Storm Arthur pounded the Southeast coast and generating a prevailing northeast wind along the entire coast. This blocks migration north. We can only guess this impact because COVID19 precautions prevented us from attaching tracking devices on red knots stopping over in Lagoa de Peixe in southern Brazil. Like Delaware Bay, LDP prepares birds for a long flight but to Delaware Bay. We have tracked red knots flying nonstop for almost 6 days to reach Delaware Bay. Attaching nanotag transmitters in Brazil would have helped us understand the impact of the storm on the birds. Instead, we must guess to what extent tropical storm Arthur impaired migration. By the Numbers

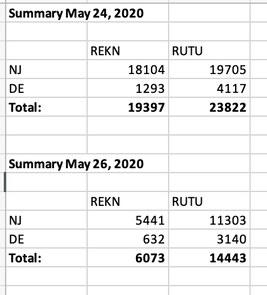

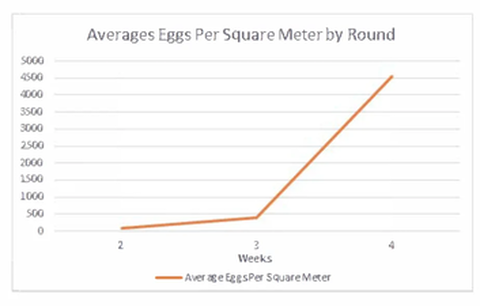

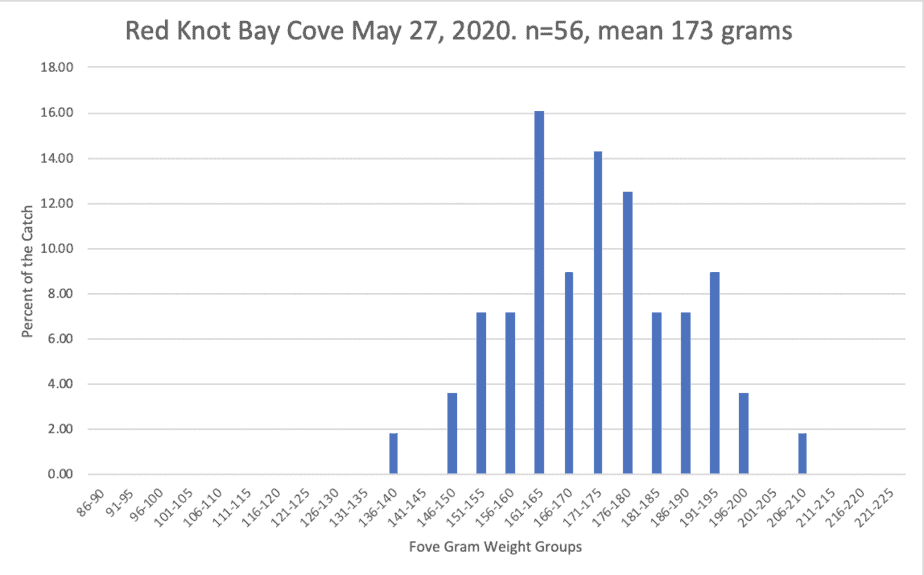

Delaware Bay bay-wide count of red knots and ruddy turnstones Delaware Bay bay-wide count of red knots and ruddy turnstones The answer came by May 26 when we did our second all bay count (only 2 days later) and found only 6000 knots. Our subsequent search turned up less each day. Today we saw about 200 on the NJ side. This suggests that not only had the large group left, but so did all the others. At the same time all of this was happening on the bay, we also saw 6500 red knots roosting in Stone Harbor during the second week of May. That number dropped to 2000 then finally to about 500. Were these part of the birds found in the May 24th survey? We have also received reports of Red knots in other places along the Atlantic Coast NJ, like Malibu Beach NJ and Forsythe USFWS Refuge suggesting birds moved from the bay to Atlantic Coast sites where they could feed on clams and mussel spat. Although sufficient for birds needing only modest weight gains, it is unlikely to satisfy the needs of the long-distance knots that must recover large amounts of weight to continue their migratory flight. Leaving Delaware Bay for Other Places Horseshoe crabs eggs counted in the last three weeks of May 2020 Horseshoe crabs eggs counted in the last three weeks of May 2020 From all this, we conclude the pulse of birds, seen in our first count came late to the bay were delayed by Tropical Storm Arthur, arrived and found few eggs, then left for other places along the Atlantic Coast. Still, the departure puzzles us. Weather slowed crabs spawning until four days ago, and then water warmed enough to stimulate dense crab spawning in more areas and higher numbers. The last few days have been epic, as though the delay had pent up the need to spawn. Crab digs now pockmark most beaches and shoals. Our egg count shows this sudden increase starting at about May 24. The bay water temperature at the Cape May Buoy explains this change in spawning intensity. It showed water temperature reaching the threshold to elicit a good spawn at about the same time we saw more spawning and counted more eggs. Yet, most beaches remained empty of birds. We made a catch of red knot on May 27, from among a very small group of knots. This sample would describe the weight gained by red knots that had been in the bay for the last few weeks. 70% of the red knots weighed less than what they need to fly to the Arctic and successfully breed or 180 grams. Yet all are gone by today May 29th. Why did they leave?

Read more about the work Dr. Larry J. Niles has done this year with monitoring bird migration through the Delaware Bay in these posts.

Work to restore horseshoe crab habitat along the Delaware Bay got off to a chilly and wet start today at Cooks Beach, Middle Township, Cape May County. Our ongoing monitoring has shown that Cooks Beach is the heart of the multi-beach complex and frequented by foraging shorebirds and spawning horseshoe crabs. The restoration effort at Cooks Beach will add up to 5,000 cy of sand to the beach, strengthen the vegetated berm, and complete the last oyster reef in a series of reefs started last year.

Last year we placed sand on Cooks Beach and constructed several reef structures but we are returning this year because Cooks serves as a feeder beach that provides much needed sand to adjacent beaches from Reeds to Pierces Point. Also, we have shown that the growing shoals located at the mouths of creeks within this multi-beach complex have substantially increased the available horseshoe crab breeding habitat from sand placed at Cooks Beach. This availability has led to proportionally more horseshoe crab eggs made available to foraging shorebirds within the complex. Since the life of our restoration projects on Delaware Bay, we have restored beaches throughout the length of the Bayshore in NJ. With limited funds for restoration, we have focused our attention on the beaches most important to shorebirds and horseshoe crabs. Five beaches within a multi-beach complex which includes Reeds, Cooks, Kimbles, Baycove, and Pierces Point have proven to be the most productive of all bay beaches for shorebirds, especially the red knot. The value of the work on any one beach within this multi-beach complex greatly benefits the sustainability and future growth of shorebird and horseshoe crab populations. For the last five years, most red knots on Delaware Bay used the multi-beach complex that we have tirelessly worked to restore. Last year our efforts were rewarded when it was shown that 29,000 of the 31,000 red knots that visited Delaware Bay to feed before continuing to the Artic, fed within the multi-beach complex. Rebuilding beaches for Horseshoe CrabsWith a great deal of cooperation from the state and federal regulators we were able to get our beach restoration permits in place and the sand placement completed before the horseshoe crabs arrived.

SHORT FORM VIDEOS ARE GREAT FOR STORYTELLING.Every now and then we put together short videos while we work on projects or someone working with us will put one together. We thought we'd share a couple of recent videos that we think are pretty great. The first video was put together by our friends at Apex Imagery. It follows the construction of a reef build from an aerial perspective - really cool. This was is from our Shell-a-Bration, at Dyer's Cove in March of last year. If this looks like a neat way to spend an afternoon shoot us an email and we'll be sure to let you know when we start building reefs in 2019. The second video was put together by Julie from the Society's habitat restoration department. It's a POV video of the work that went into the construction of a coir log containment area for our marsh restoration project at Thompsons Beach. If you're interested in more info on that project check out some of our earlier blog posts. We have a bunch of new projects kicking off in 2019 that will require a lot of help to get done, if you want to help click "contact" in the menu and send us your details. We'd love to see you out there on the beach.

The American Littoral Society has been awarded grant funds from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to work on three more projects along the Delaware Bay. This makes 2019 the sixth consecutive year the Littoral Society will be working on habitat restoration projects in the Bayshore region.

The projects undertaken so far have included beach restoration, intertidal reefs, and marsh restoration. We have focused on making beaches along the Bay better suited for spawning horseshoe crabs and foraging migratory birds. Along the way we have learned a great deal from our monitoring efforts and work to incorporate these lessons into new projects.

Over the coming year we will be working on improving the beach habitat at Cook's Beach and Baycove Beach in Middle Township, Cape May County. These projects will add sand to the beaches and help preserve the beach face with the addition of oyster reefs.

Additionally, we will be working on the planning and permitting of future projects at the mouth of the Maurice River. Projects will focus on preserving Basket Flats and the area in front of the Matt's Landing dikes. The long-term goal of these projects is to improve habitats, maintain the economic viability of businesses on the Maurice, and provide protection for the communities at the mouth of the Maurice.

Written by Larry Niles, Niles-Smith Conservation Services For more great info on the Delaware Bay check out Larry's blog about ecology and wildlife conservation, A Rube with a View. A Failure to LearnOur work on Thompson's marsh covers only a tiny patch of the Delaware Bay marsh. One might say our one-acre restoration is too small to have any significant impact, so why do it? Big projects are certainly more important. And ultimately we will need many of them to realize Governor Murphy's recently announced coastal resiliency policy initiative. But big projects can fail big and waste taxpayer dollars. The Delaware Bay has seen a number of these failed expensive projects, like the shoreline restoration of Sea Breeze where $6 million in state-funded cinder blocks lie uselessly on the shore of this now abandoned town. Indeed unfinished protection in the mouth of the Maurice River, where a sunken barge is all that remains of a failed effort to stop the erosion of Basket Flats and the other adjacent wetlands that protect the towns of Port Norris and Heislerville. Working With NatureThese resiliency failures occurred for many reasons, but an important one was failing to take advantage of natural defenses to augment protection. Why defeat the Bay with concrete and steel when you can achieve the same goal with high functioning marsh and well-protected beaches? Easier said than done of course which points to the second reason for recurring failure - no one monitored the projects in order to describe the conditions before during and after the project. Someone engineered the project, someone else got a contract to construct it and then everyone walked away. No one the wiser. Or they did monitor the project but never used the data in a way that described the success or failure of the work and its ultimate ecological impact. Perhaps this is the most the failure because the experience provided no clues on how to carry out the next project. Each new project becomes a gamble or worse useless in the face of an ever-growing threat. Instead, the failed projects speak for themselves, apocalyptic-like reminders of our inability to protect the wildlife and people of Delaware Bay. Start Small and LearnSo our project provides more than a one-acre fix for abandoned salt hay farms. It also helps us understand the most cost-effective way of conducting larger more expensive projects and create innovations that can improve ecological condition. Better to start small and learn. First the problem. Over 10,000 acres of Delaware Bay marsh remains damaged after a wholesale abandonment of at least a century and a half of restricting tidal flow with earthen dikes. The dikes blocked sediment-rich tidal waters to allow salt hay or spartina patens to grow and cut for hay. Each cutting removed vital biomass. Without new sediment or biomass, marsh elevations fell about 2 feet but in some areas as much as 5 feet. Without the dikes, the sea scoured the newly exposed and sparsely vegetated wetlands leaving bare mud as shown in the photos of my previous blog. Thompson Marsh could have turned into a big mud flat like Cox Meadow endangering the people in the town of Heislerville NJ. Instead, the state allowed PSEG to avoid the cost of a new cooling tower by managing wetlands. They hoped the addition of productive marsh would offset the loss of fish killed by increased use of cooling seawater. One can see the work in the following series of photos. The PSEG engineers dredged a new watershed of small creeks allowing a slower draining and flooding of the marsh. It worked. The wetland began recovering slowly over time. New inflow of sediment and the sparse growth of Spartina alterniflora or marsh cord grass built new biomass. The papers of the restoration team spoke of recovery. Unfortunately, sea level rise dashed those hopes. It matched the elevation gained by a renewed marsh. The higher volume of water and more frequent storms scoured mud and sand in the mouth of the creeks. It also eroded creek banks thus increased tidal flow. There is spartina growing over much of the restored area but at a much lower density and slower growing than cordgrass at the proper elevation. A New Start on Thompsons MarshFor Thompsons and many of the once farmed tidal wetlands on Delaware Bay, the only hope is to start rebuilding elevation with new mud. Our wetlands restoration is an experiment with two goals. First how best to manage an old hay farm back to a stable, productive marsh? The second how to do at a practical cost? For example our dikes. In the old days and the PSEG work, workers made new dikes by digging into the marsh. This damaged marsh and created new ditches for water to scour away sediment. We use Coir logs, or 10 feet long 24-inch diameter jute bags of coconut fiber, to form our dikes. They are cheaper than digging and will gradually degrade into the marsh. Most important we avoid damaging the fragile wetland. Managers have used Coir logs elsewhere to confine mud but not in Delaware Bay with its 7-foot tide swing. If successful we will have a low cost and an environmentally friendly solution that can be scaled up to larger areas, one of our top goals.

Restoration Is ExperimentalIn a way all restoration is experimental. Even when done successfully conditions matter enough to make every job different. Restoring a wetland on the gulf coast where tides rise no higher than 2 feet, is far different than Delaware Bay, where the tide can swing 8 feet in a daily cycle. In Florida, winters can serve up a nippy 50's while on Delaware Bay the weather can turn genuinely foul. The bay freezes in most years and thick ice moved by daily tidal cycle can scour and destroy. So previous experience provides some guidance for the wetland biologist, but one must always pursue their restoration as something unique requiring great care and sound monitoring.

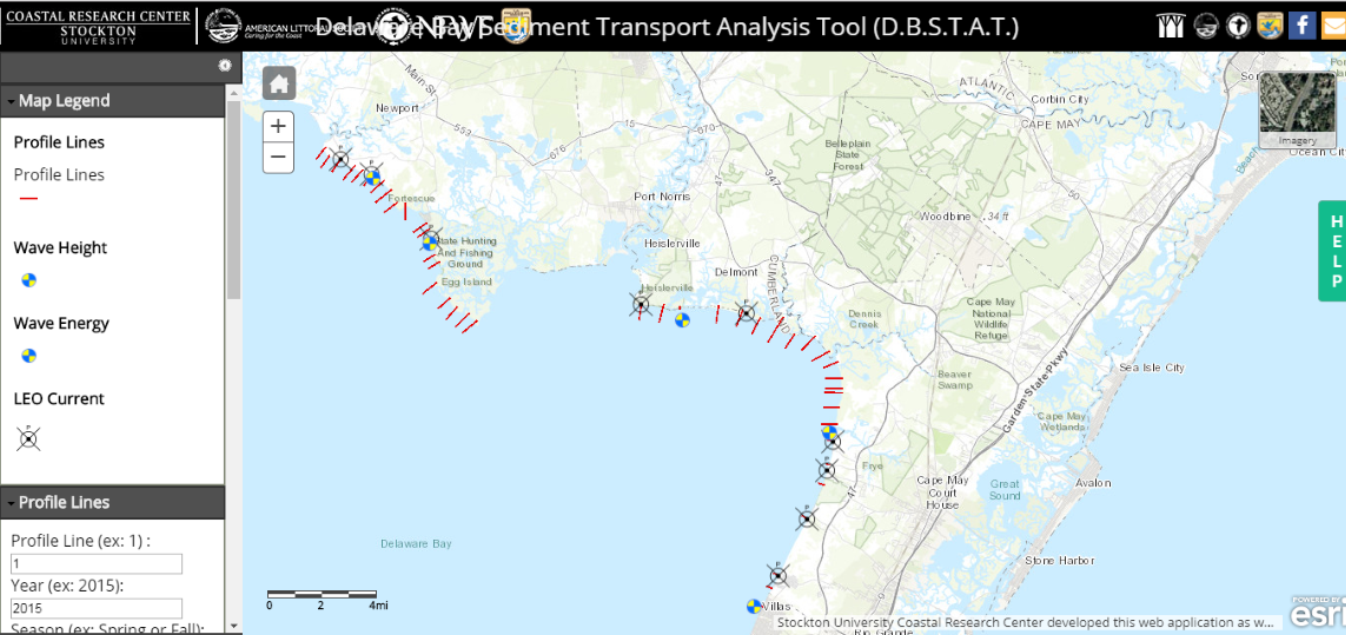

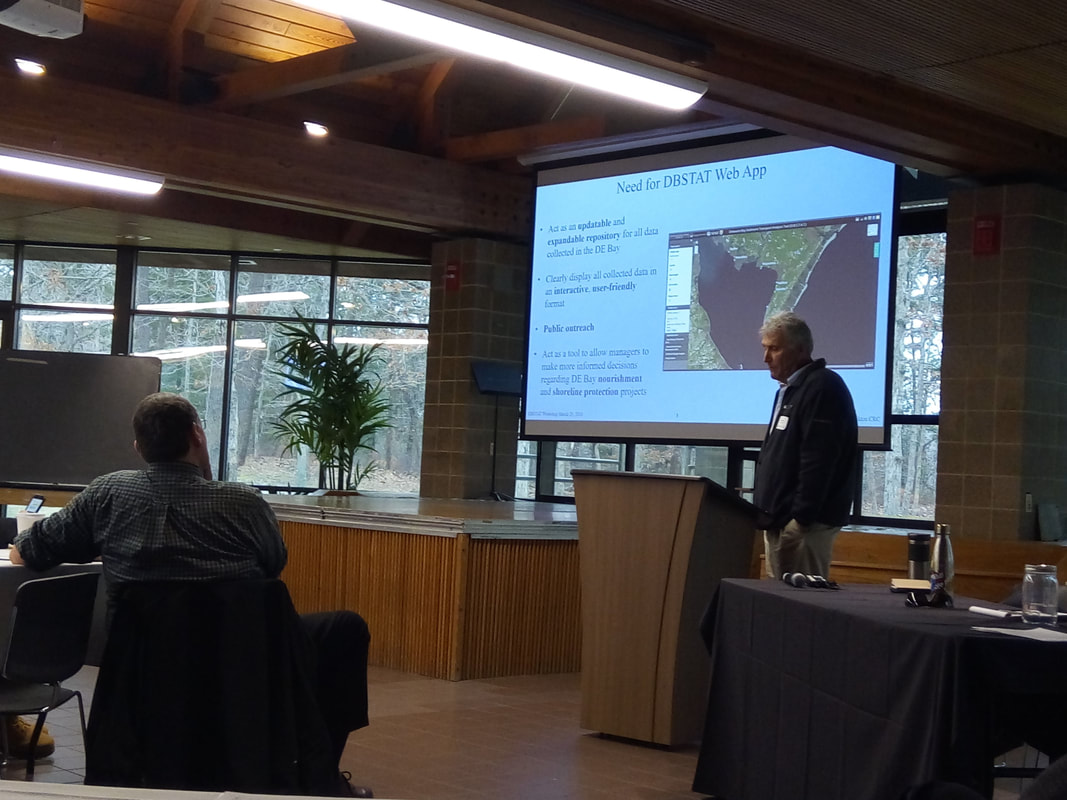

This is why we must conduct this experiment in marsh restoration. Written by Larry Niles, Niles-Smith Conservation Services For more great info on the Delaware Bay check out Larry's blog about ecology and wildlife conservation, A Rube with a View. Centuries of Farming the Marsh has Left an enduring LegacyCenturies of cutting salt marsh vegetation as hay in Delaware Bay left an enduring legacy fraught with danger. Farmer diked the tidal wetlands starving the marsh of sediment and accelerating natural decomposition. Marsh levels fell relative to the tide, so when the farming ended in the 60's the bay rapidly eroded the damaged and fragile marsh. Large areas of the Bayshore were lost and the erosion continues to the day, but now exacerbated by a 4mm yearly rise in sea levels caused by climate change. This week a partnership of experts led by American Littoral Society and Niles Smith Conservation will begin the first restoration of a Delaware Bay marsh damaged by salt hay farming. The goal of the project is to restore 1.8 feet of mud lost by farming with new sediment dredged from an adjacent creek choked with mud from the eroded wetlands it drains. We will create our own dike made of vegetative logs or Coir Logs, and begin to reverse the process started 200 years ago. We intend to bring the marsh height back to it's naturally stable level - marsh vegetation just barely flooded on a normal tide. The productivity of the wetland will improve and more importantly it will be stable providing long-term resiliency. A New Kind of Marsh StewardshipOur second goal is to conduct a restoration experiment. Over the next months, we will slowly raise with the height of this marsh at first to assess our method. Will the Coir Logs provide enough of a barrier to contain the mud? How much drainage is necessary to ensure a gradual dewatering of the slurry of mud and water pumped into the contained area. Finally, how will it resist the winter and then how will it regrow? These questions cannot be answered with just books or judgment. We are farmers assessing conditions for a good crop of spartina alterniflora. This American Littoral Society Project will create structurally sound but ecologically beneficial solution to a complex problem plaguing the bay. Our project offers hope for a long-lasting solution by making new tools to accomplish it. If anyone would like to help with this project, please contact Shane Godshall. By Quinn Whitesall, Habitat Restoration Technician, American Littoral Society  Nate Gable, U.S. Veteran intern of the American Littoral Society, recording beach characteristics. Nate Gable, U.S. Veteran intern of the American Littoral Society, recording beach characteristics. There is little understanding of sand transport patterns in the Delaware Bay but in order to ensure ongoing sustainability of restored sites, this knowledge is needed. The ultimate goal is to identify “feeder beaches” where sand can be placed and allowed to move to other beaches via natural sediment transport pathways. In cooperation with the Stockton University Coastal Research Center and USGS, for each beach restoration project, data on waves, tides, currents and sedimentary characteristics has been gathered to arrive at estimates of entrainment and longshore sediment transport potential at the target restoration sites and to aid in that decision on restoration design (geometry, timing and sedimentary characteristics) and need for structure alteration or removal. The Delaware Bay Sediment Transport Analysis Tool (DBSTAT) is a web-based application that has been developed by the Stockton University Coastal Research Center to aid in the identification of optimal locations in the bay for fill placement to enhance habitat. The tool can also assess the importance of subsequent modification to increase resilience. DBSTAT visually displays preliminary Sediment Budget Analysis System (SBAS) results for Delaware Bay (Cape May and Cumberland Counties) using data from the Delaware Bay Sediment Transport Study. On March 29, the Littoral Society and partners officially launched DBSTAT to the public at a workshop hosted by Stockton University. In attendance were representatives from NJDEP, FEMA, USACE, USFWS, local municipalities, and engineering firms. The workshop began with opening remarks from Tim Dillingham, Executive Director of the American Littoral Society, regarding the need for restoration work in the Delaware Bay following Hurricane Sandy. Captain Al Modjeski, Habitat Restoration Director of the American Littoral Society, provided a brief overview of the beach restoration work, reef builds, and the community outreach that has taken place in the last four years. Following the Littoral Society’s project overview, Dr. Joe Smith of LJ Niles Associates provided results on the improvement of habitat quality for horseshoe crabs and shorebirds and guidance for future beach restoration projects. After lunch and a viewing of “New Jersey’s Hidden Coast,” an interactive tutorial of DBSTAT was provided by Mat Suran and Nick Dicosmo of Stockton University. Attendees were invited to follow along on their personal devices and provide feedback on the tool. The workshop concluded with the next phases in the development of this tool and the need for additional funding to fill data gaps. To access the Delaware Bay Sediment Transport Analysis Tool (DBSTAT), visit https://crcgis2.stockton.edu/dbstat/

By Quinn Whitesall, Habitat Restoration Technician, American Littoral Society The deep freeze that took place in Delaware Bay this month created some of the harshest conditions our oyster reefs have ever experienced. For over a week, solid ice covered portions of the Bay and the shoreline, and in some places the ice was over three feet thick. We wanted to know how the ice and tide would impact our intertidal reefs and one of the best spots to assess these effects was at Veterans Reef located slightly offshore Reeds Beach. Shane, the Delaware Bay Habitat Restoration Coordinator pictured in the photo below, and I, arrived at Reeds Beach where we were greeted by a landscape that was more reminiscent of the treeless Arctic tundra rather than that of the open water of the Delaware Bay. We were shocked that the reef was not visible at all and feared the worst for our oysters and the reef itself. We decided we would need to come back at low tide after the thaw and assess any damage to this very important ecological community. Once temperatures rose and the ice melted away into memory, I once again took a trip to Veterans Reef to re-assess possible damage from the ice. Overall, the reef structure was intact which further provided evidence on the heightened resiliency of whelk shell when used as a foundation for intertidal reefs and the importance of interstitial space and the shape of the shell, not just for providing habitat or species refugia, but to possibly combat impact of ice with its asymmetrical surface. Condition of the reef and the health of the oyster community appeared to relatively unaffected by the ice and current observations were similar to those of our last visual inspection from the fall. A few reef segments appeared to be unaffected at all. Out of 23 reef segments at Veterans Reef, only one seemed to have been impacted. Quite a few bags had come loose, were dislodged, and were shifted forward, most likely a result of large ice blocks moving with the tide. This was easily repairable. The outer reef was completely intact with no shell bag movement most likely because it was never exposed due to depth of water versus depth of ice. Along some segments of the reef, gapers, dead, open oysters with tissue inside, were spotted. We have identified gapers on the reefs in the past, but none were present during our fall observation. Some oysters, which were more exposed to the ice and located on the outer surface of the whelk foundation, were completely crushed, likely a result of shifting ice. However, oysters that were more sheltered between shell bags were not affected at all. Overall, it would appear that oyster mortality was rather low and intertidal oyster reefs in Delaware Bay can combat and tolerate impacts associated with ice. There will be some loss but that is understandable. This was evident with other sessile reef inhabitants, like the ribbed mussel and barnacle. Species that were more sheltered by the reef or whelk shell, were not affected, however those same species that were more exposed to the elements, like the thin-shelled ribbed mussel, were crushed by ice movement. Oddly enough, the barnacles faired well and did not seem affected at all regardless of where they were on the reef which again, like the whelk, could be a function of their asymmetrical shape. Another visual assessment will take place this spring, stay tuned!

|

Archives

April 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed